Source Excerpted From Gotehborg,

The Ming to Qing Transitional Period (1620-1683)

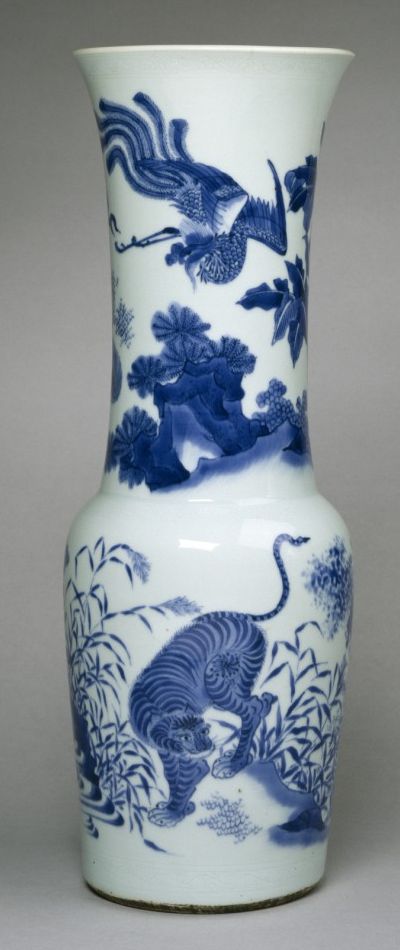

About, Porcelain Ming Transitional, Classic and typical vase of the best kind, that is usually called High Transitional.

This is the common name for the period during which the Ming dynasty has lost, and the Qing dynasty has not yet gained, control over the Imperial porcelain factory in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province.

For the sake of providing a working date, the Transitional Period in Chinese ceramics is considered to have started with the death of the Wanli emperor in 1620. It spanned the changeover from the Ming to Qing dynasty in 1644 and extended to the arrival of Zang Yingxuan as director of the imperial factories at Jingdezhen in 1683.

This stormy era in China’s history produced a fascinating conglomeration of porcelains.

Antique 17C Porcelain Ming Transitional Chrysantenum Flower Plate, Traditional wares.

Some rather routine wares that continued earlier decorative formulas were manufactured. In these tired echoes of earlier achievements one can follow the progressive change from Ming, to Qing,dynasty styles.

Nontraditional wares.

However many of the porcelains dating to the Ming portion of the Transitional Period are quite different from the conventional Chinese ceramics that had been manufactured up to this point. Some of these wares were specifically made to European or Japanese order. In many of these wares for the foreign markets, the concepts of shape and/or decoration in Chinese ceramics have been perceptibly changed: they have been determined by foreign taste as never before. Other porcelains, while not expressly made to foreign order, took the fancy of overseas buyers and found their way to Europe and Japan.

During the transitional period in the mid seventeenth century in China, for some fifty years the absence of Imperial patronage meant that a large number of highly skilled potters, artisans and craftsmen stood without means to support themselves.

This resulted in one of the most dynamic and fascinating periods in China’s porcelain history and a dramatic diversity of production.

The craftsmen now turned their attention to producing and selling to merchants and scholars on the domestic market, and into the newly-emerging export markets, notably the Japanese and the Dutch.

The various styles and motifs lends themselves to studying how the Jingdezhen potters and painters designed special porcelains to appeal to the various new customers. This in itself was nothing new to the Chinese potters. The new part was the quality of the material and the skill that could now be applied to commercial wares.

One example is the wares made for the Japanese ‘tea ceremony’. Porcelain decorated with tulips were produced for the Dutch or Turkish market. For the domestic market, the potters began to use woodblock prints illustrating domestic literature and artistic fashions into porcelain design.

One aspect that is little studied is how much in particular the Dutch with their orders, influenced the development of shapes as well decorations by their sending of models made at Delft and other Dutch artisans or for that matter the influx of Japanese ideals and ideas to the Chinese potters.

Although it actually was only one of many very different types of porcelain made in the Transitional Period, one distinctive type of porcelain is generally catalogued as “Transitional” ware. These ceramics are traditionally associated with the European primarily Dutch-markets. It must be remembered, however, that some of the finest “Transitional” wares, were obviously made for domestic use.

Transitional blue-and-white porcelains are skillfully potted and decorated in a lovely shade of deep blue that inspired the simile, “like violets in milk.” The painting has been done with a talented hand. Many of the finest objects are embellished with groups of figures in distinctive landscapes that have steep walls of rocks improbably interrupted by clouds, isolated cone- shaped mountains, an ever-present moon, and the characteristic V-shaped tufts of grass.

Notable too is the use of stiff, acanthus like leaves, as well as a tulip-shaped ornament, which was probably derived from a European source. Unlike the Ko-sometsuke and Shonsui wares, the decoration of “Transitional” wares is almost completely in Chinese taste, and there is very little foreign flavor to it. However, the forms of many pieces were adapted to Western demands: the Dutch were supplying Chinese merchants with wooden models of the shapes they wanted copied as early as 1635.

A few examples of “Transitional” wares have inscriptions that include the reign title of a Ming-dynasty emperor along with a cyclical date. From these dated pieces, as well as other documentary evidence, we can attribute “Transitional” wares to as early as 1625. Although the majority of these ceramics were probably made in the Chongzhen period (1628-44), the type continued in a somewhat modified form into the early Qing dynasty.

In 1972, some fragments of typical “Transitional” wares were found on the Little Bahamas Bank by Willard Bascom, an oceanographer. He has identified these fragments, and other material found with them, as coming from the wreck of Nuestra Senora de la Maravillas. This was the second-in-command ship, or almiranta, of a Spanish royal armada of treasure galleons out of Havana, Cuba; it sank on 4 January 1656.