Chinese Robes Depicted In Ancestral Portraits

Chinese Imperial-Court Robes In Portraiture, An Ignored Art

Chinese Imperial-Court Robes have become in recent years among the most collected of all Chinese art forms from the Qing and earlier dynasties. While none have reached the stratospherically phrenzied levels of Imperial porcelains, jades and ancient bronzes. They have enjoyed a considerable amount of competition among collectors whenever a fine example reaches the market. The best examples now selling well into six figures, something that seemed impossible a few decades ago. Chinese Imperial-Court Robes in portraits seem to be an overlooked and under appreciated cultural art.

Portraits Depicting Robed Figures Who Defined Chinese Culture

When it comes to what are commonly referred to as "Ancestral Portraits" collectors and institutions seem to have relegated these paintings to a "minor art" category. As a result, they represent are a relative bargain in the market when compared to the dozens of other Chinese art forms being chased across the globe. The quality, spirit and content of these paintings are often the very embodiments of Chinese culture on a par with any of the arts from the same periods. Within them, you will see aspects of Chinese culture unavailable through any other media. These faithfully done paintings capture a moment in time and as historical documents present a visual understanding of who they were, what their lives were like and what influence they had on China's cultural history. In short you have the opportunity to quite literally come face to face with Chinese culture.

A VERY Brief History of the Chinese And Silk

The first silk worms were cultivated in China around 5,000 years ago (Circa 3,000 BC) according to the results of tomb excavations in Neolithic sites in north central China. Along with the silk were found bone needles and other implements essential for the making of silk. Chinese silk is harvested from the cocoons of the Bombyx mori moth by drawing out with great care long threads coiled within. To make the very best silk, these moths were and still are today fed a diet of mulberry leaves. During the process, the health and well-being of these creatures were carefully monitored to ensure a consistent top quality product.

The early importance of silk in Chinese culture can be verified y the discovery of gilt bronze models of silkworms found in Han Dynasty tombs (3rd-2nd C. BC). In time, cultivating silk due to it's commercial popularity grew from small-scale family cottage industries to mass production. By the Shang dynasaty (1750-1100 BC), silk was exported throughout Asia and over the centuries spanned the globe as the rarest of all textiles. Warm, comfortable and beautiful, silk was king.

Excavations of tombs ranging from the earliest days through the Warring States (4th C. BC), Western Han(206BC-220AD), Sung, Ming and Qing dynasties all verify the consistent never ending demand and appreciation of silk. Today archeologists have managed to gather fragments of the earliest robes, jade carvings silk worms, drawings and carvings of figures in elaborate silk damasks have been found throughout China.

Chinese Imperial-Court Robes of the Ming and Qing

The designs and styles of Chinese imperial-court robes of the Ming and Qing dynasty were produced and styled based on a formal and well-established system based on rank within the government or social position. Codes of "Official Dress" were issued by the court and modified from time to time during these periods, always dictated by a tight social structure kept in close alignment with the bureaucracy. At a glance, it was possible to determine one's rank and level of nobility by the clearly delineated patterns, colors and emblems worn by both men and women. This visual hierarchy according to dress became an increasingly essential during the Qing dynasty in particular among government officials.

Everything worn by government officials was prescribed by the dress code, including hats, collars, surcoats, belts, shoes and so forth. The style of the Ming red robes of voluminous design and broad sleeves gave way in the Qing dynasty to narrow sleeves, side slits and trousers. The Qing also replaced the use of rich deep reds with the use of yellow for the Imperial family.

Ch'ao-Fu "The Robe of State"

The most formal of all Chinese Imperial-court tobes were the Ch'ao-Fu, also known as "the Robe of State". These were worn only for the most formal and solemn occasions in the court. Few of these robes have survived

Chi-Fu "Dragon Robes"

The second tier of dress known as "Semi-formal robes"which include the classic Dragon motif robes most often seen today. Fortunately, many did survive in fairly large numbers, in particular, those from the second half of the 19th C.

Ch'ang-fu " Informal Robes"

These are the least formal of the Chinese Imperial-court robes falling under the dress guidelines and were not to be worn during any ceremonies of the court. These are not the same as the typical un-regulated robes worn by the typical citizen or well to do merchant's family.

NOTE: All paintings illustrated are in the collection of the Freer-Sackler Gallery Washington DC unless otherwise noted.

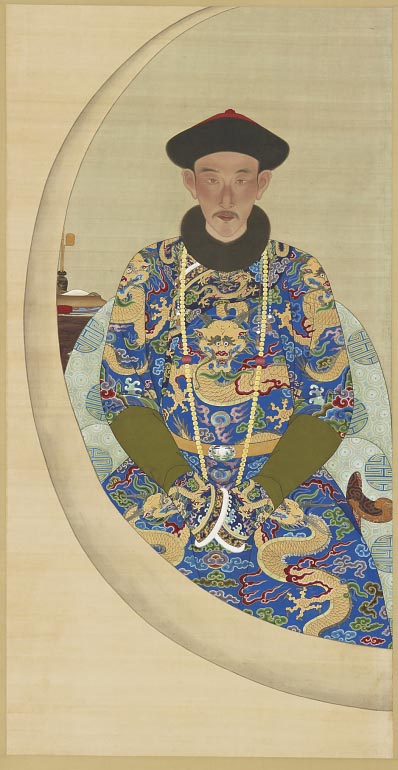

Yinxiang, Prince Yi (1686–1730),

Prince Yi , born in 1686 the 13th son of the Kangxi Emporer and younger brother of Yinzhen who assumed the name Yongzheng and ascended to the throne upon the death of their father in December of 1722. During the ten years prior to Kangxi's death, Yi had been imprisoned by the Emporer. Yongzheng released him upon Kangxi's death. For the rest of his life Yi served as a devoted loyalist to Yongzheng, he died after years of ill health in 1930.

This portrait is striking in its informality and relaxed posture of the sitter. His shoulders sloped downward slightly but wearing a 12 dragon robe with fur collar and red topped fur brimmed hat and imperial court necklace of white jade with coral beads.

Lady Guan

A high ranking Manchurian "bannerwoman". A similar painting was also done of her husband. Bannerwomen and Bannermen were considered a special class of noblemen and women, their titles evolving from a system developed under the "8 Banners" during the Ming dynasty. Eventually the Han-Ming and Manchu-Qing banners were fully merged under the Yongzheng emperor.

An extremely elegant painting: The portrait is probably posthumous due to the execution of her face which is a bit stiff and at variance with the then tradition of "realism" when doing portraits. The painting is dated 1716 and identifies her as a "Dame-consort, 1st rank". Wearing winter robe with fur edged trimmed court collar and string of coral and jade necklace. She is also wearing 3 sets of earrings, quite unusual as most women of her rank wore only two.

Formal Portrait of Daisan (1583 - 1648)

Daisan, an important Chinese general and uncle to Qing Emporer Shunzhi (1638-1661). His brother Hong Taiji was the first Qing emperor to assume the title but was later given posthumously to their father Nurhaci a Jurchen chieftain who is historically credited with defeating the Ming and forming what became formally the Qing dynasty.

It is believed the painting was executed during the second half of the 18th C. under the reign Qianlong in memory of his great, great uncle. The robe depicts elements often associated with that of the early Qing, however, the sleeves and collar are more in line with traditional robes done during the 18th C.

Regent Oboi, Kangxi's Powerful Regent

Oboi, rose to power during the reign of Shunzhi and was appointed by the emperor to serve with three others as the Kangxi emperor's "Regent" until he was 16 and able to rule. Oboi was a legendarily power hungry official who was sentenced to prison by Kangxi when he assumed the throne at the age of 14, two years early, out of fear Oboi would solidify too much power. He died in prison shortly after being sentenced. During the early 18th C., Kangxi rehabilitated Oboi's image by giving credit for his valiant efforts in helping establishing the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) through his earlier military exploits.

The painting was done during the 19th C., presumably by his descendents, to venerate their ancestor. Unlike other portraits which are usually peaceful, his evokes a fierce representation in keeping with his historic reputation for ruthlessness. His hat fitted with a single eye Peacock feather known as lingyu indicates how highly he was regarded by the imperial house. His robe, with large animated dragons in bold contrast further gives the viewer a sense of his legendary power.

Yu Chenglong (1617-1684) Favorite Civil Servant

Yu Chenglong a legendary Civil Servent who began his service under the Shunzhu Emperor and later under the Kangxi Emporer. During his long career, he represented for many in China the epitome of what a good civil servant should be. He built schools and worked tirelessly to serve the Qing leadership. During Kangxi's 19th year he promoted Yu to Provincial Governor of Zhili, with more promotions to come as his integrity and efforts on behalf of the common people became the thing of folklore. He was by all accounts completely immune to bribery and was known to intervene in cases where an injustice was about to happen. Following his death, the Kangxi Emporer bestowed upon him the posthumous title of “Clean and Honest”.

The painting depicting Yu Chenglong is a fairly simple rendering in a comparatively simple robe despite his position. According to historic notes from his time, following his death he owned no elegant silk robes, not even like the simple one depicted. The only clothing found was a common coarse cloth robe. The clear blue robe illustrated with a simple and important rank badge framed by an oversize court necklace of jade and coral serve as a statement to his modesty and importance.

Yang Hong

When viewing Chinese Imperial-court robes of the Ming dynasty in portraiture few will match up to the quality, power and elegance captured by the artist in the of Yang Hong. Dressed in his formal helmet, his face superbly rendered in classic Ming style wrapped in the deep red voluminous silks and trimmed in blue so closely identified with the dynasty.

Yunti, Prince XUN (1688-1756)

Yunti or Prince Xun was the 14th son of the emperor Kangxi and brother to future emperor Yongzheng. Among the highlights of Yunti's life was his reinstalling of the Dhali Lama after recapturing Lhasa with over 300,000 soldiers from the Dzungar general Tsering Dondub. Kangxi titled him as "Great General Who Pacifies The Enemy". Following Kangxi's death, Yinti's brother the new emperor Yongzheng placed Yinti under house arrest for the duration of his reign. The new emperor feared his brother posed a threat, stripping him of his rank and incarcerating him solved his potential problem. Upon Youngzheng's death in 1735, Yinti was released and given a title "Prince Xunqin of the Second Rank" by his nephew Qianlong (1735-1796).

The painting depicts aged Prince Xunqian and his young wife Lady Jinse (age 14). Interestingly the face of Yinti is well defined and detailed showing his age in a very realistic fashion. His wife's face, however, is nearly lifeless and generic looking. The reason is a simple one, artists during this era were rarely ever allowed to see the actual faces of the women they painted. As a consequence, the facial features were left to the artist's own imagination to create an idealised version of Chinese women's beauty. The couple depicted wearing nearly matching Chi-Fu semi-formal sur coats over their robes. She with a fine bejeweled Kingfisher headdress with both wearing coral and lapis court necklaces. Seated on a coach fitted with marble dream stones. An interesting feature of most of these paintings is the men's feet are nearly always visible, while the women's are not.

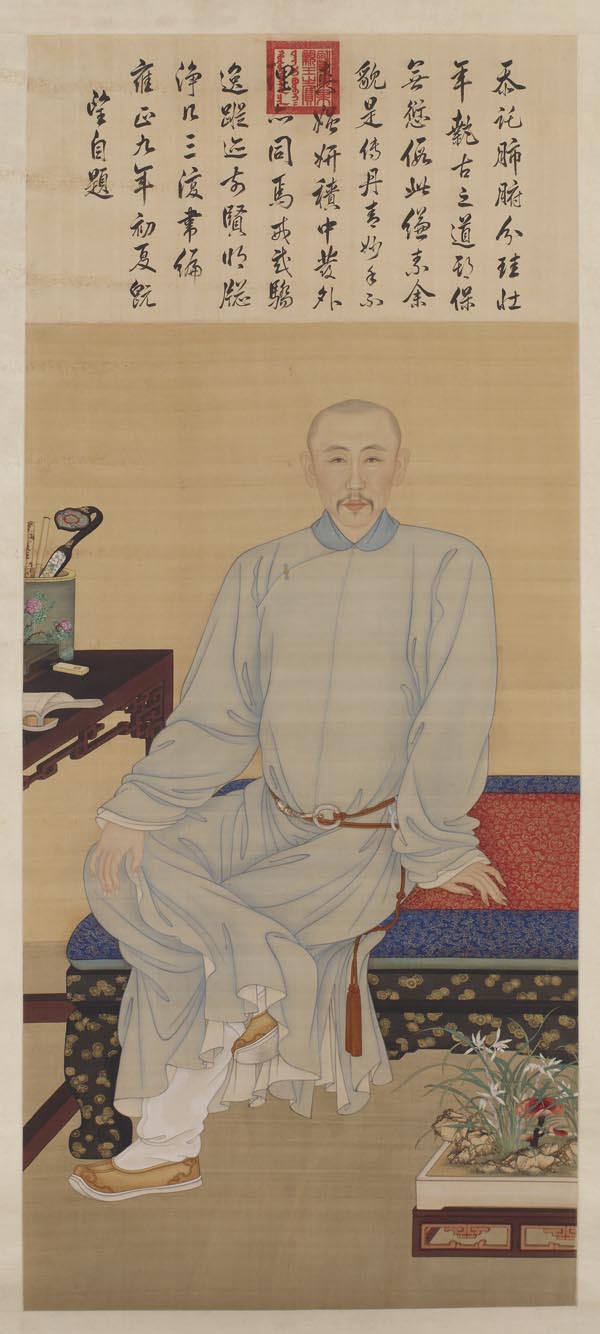

Three Portraits of Yinli, Prince Guo

Yunli, the 17th son of the Kangxi emperor was born in 1697. At birth, his name was "Yinli" and was later changed when his half brother Yinzhen ascended the throne assuming the name Yongzheng, at which time Yinli's name became Yunli. The change was needed as his brother's Imperial name was now the same as his.

Yunli, unlike his brothers, was not particularly politically motivated by all indications and opted to follow a path of intellectual pursuits. In 1722 Yongzheng granted his brother the title "Prince Guo of the Second Rank", after six years of faithful service he was elevated again to "Prince Guo First Rank". Shortly before Yonzheng's death, Yunli was appointed to support the next heir to the throne Hongli , soon to be known as the Qianlong emperor.

Interestingly Yunli loved having his portrait done and were usually done by one artist Mangguri (1672–1736) .

Unlike the portraits of other members of the Imperial house, Yunli's were of a much less formal nature depicting him more as a relaxed intellectual with an appreciation of beauty and nature. This is particularly well illustrated in the first of the three portraits. The Prince is seated casually upon a cushioned bench in a scholar's studio in the simplest of dress. Before him, a bulb tray of blossoming cymbidium orchid. In China the orchid, since the time of Confucius (551-479 BCE), has been associated with the virtuous moral men who's value is often overlooked by those in power. For centuries, Chinese literature has contained numerous references to the orchid and it's many meanings such as friendship, loyalty, integrity and purity.

The poem above the portrait written by Yunli reads:

Humbled that through my kinship to the throne,

I was allotted a scepter in the prime of life,

I shall hold fast to the Way of antiquity,

And hope to preserve it without transgression.

Availing himself of this fine white silk,

That my figure may be transmitted on it,

The painter was indeed a marvelous hand,

Who erred in neither ugliness or beauty,

What is stored within is displayed without,

He has captured here my character as well.

Refraining from any wanton extravagance,

I shall follow in the footsteps of the former sages,

And by the bright window, at my clean desk,

Thrice replace the worn-out bindings on my books.

The second painting depicts Yunli wearing an unadorned sur-coat before a backdrop in the style of the Yuanmingyuan Summer Palace, portions of which were built in the manner of a French Chateau. This unusual portrait illustrates the fashion and popularity and appreciation of French culture within the court.

The last, a Springtime portrait depicts Yunli seated wearing modest dress in a naturalistic landscape with his attendants, one bearing a bundle of books and the other bringing him tea. In the background, an aged Willow tree with budding leaves, a symbol of renewal (Spring), immortality and virility in Chinese culture. In the foreground a scholar's rock with butterflies.

Yunli died on March 21,1738, three days short of his 41st birthday.

Lirongbao and His Wife Wearing Chinese Imperial-Court Robes

Lirongbao and his wife were the parents of the Qianlong emperor's first Empress Consort Xiaoxianchun (1712-1748).

Being the mother and father inlaw regardless of their personal positions before the marriage (Lirongbao Supervisor of Chahar Province) elevated them in time to the highest rankings possible within the Imperial house. Curiously the mother is not wearing court necklace which she would have been entitled to, given her position.

Lingbao is wearing a sur-coat over his Ch'ao-Fu five claw dragon robe with a crane rank badge, a ranking he was given posthumously. His wife,clad also in the highest level of formal court dress with massive five claw dragons .

Portrait of Empress Xiaoxianchun

Empress Xiaoxianchun, the first Empress (1711-1748) of the Qianlong Emperor, the daughter of Lirongbao. She married the future emperor in 1727 under the reign on his father Yongzheng who died in 1735.

The power of this exceptional painting and who the sitter is, is superbly conveyed by the artist. The painting was executed most likely in the Court or Palace Workshops after 1735. Her formal Ch'ao-Fu robe with numerous large animated dragons, the robe fully and perfectly displayed in a bell-like fashion, her necklaces of coral and jade with coral and pearl earrings and headdress are reserved strictly for only the highest ranked family members.

Few other extant portraits depict Chinese Imperial-court robes with the presence of this example, with the possible exception of some depicting the emperor Qianlong .

Portrait of an empress, possibly Xiaoxianchun, wife of Emperor Qianlong adorned in the among the finest of Imperial court robes.

Painting: Ink and color on silk

108 1/4 x 51 9/16 inches (275 x 131 cm)

Gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Sturgis Hinds, 1956

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

E33619